By Lisa Taylor

I don’t know if Lisa LaFlamme’s dismissal was a result of ageism.

I do know it’s a big deal that, within minutes of her Twitter sign-off, Canadians from coast to coast to coast began talking about ageism.

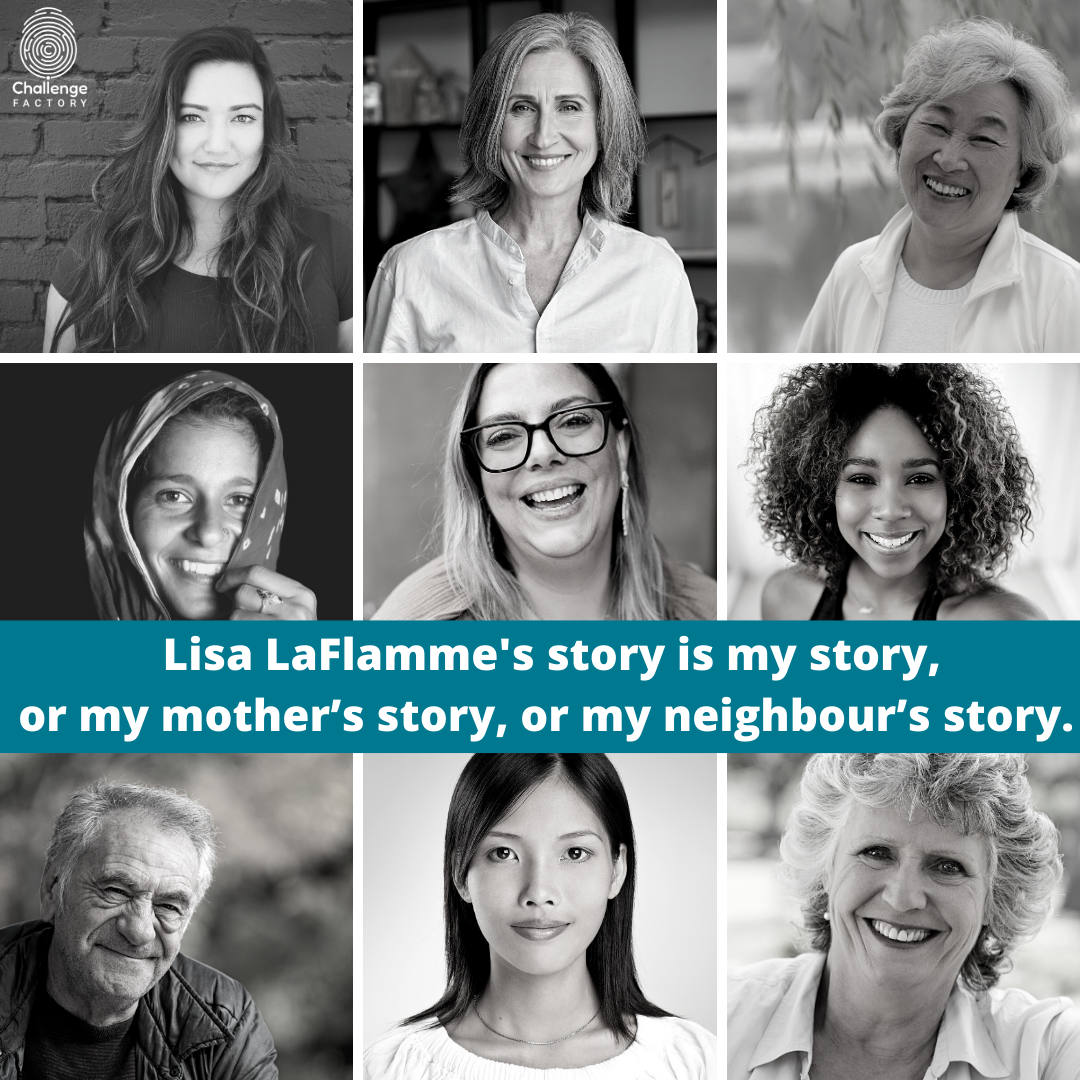

In that moment, thousands of Canadians related to Lisa LaFlamme on a human level and found themselves, suddenly, remarkably, visible.

“Her story is my story, or my mother’s story, or my neighbour’s story.”

Ageism is so prevalent in workplaces that it is a common and shared experience—even if, or perhaps because, it is so rarely discussed.

More than a week later, and Lisa LaFlamme is still the story in Canada. On Monday, Dove commercialized the discussion, launching a campaign that encourages everyone to “go grey” by changing their profile pictures and logos to greyscale.

The mixed reactions to this campaign have been interesting. Some laud the company for taking a stand. Others suggest that altering profile photos to appear grey-haired is unnecessary, since there are millions of naturally grey-haired Canadians ready to share their photos unaltered. They also criticize that the model in the campaign is a younger brunette using a greyscale filter.

None of us in the general public truly know the extent to which ageism (or sexism) were factors in Lisa LaFlamme’s dismissal. But the reaction does indicate a few things that we know for sure:

- Ageism is so commonplace that the story became personal for a large number of Canadians.

- A groundswell of personal stories and accounts has dominated the media and conversations that Canadians are having.

- Dove’s choice not to use a gray-haired older model is strategic. It reinforces that ageism is everyone’s problem.

- Prejudice cannot be fought only with firsthand stories of and by the impacted group.

This last point is the most powerful and important. Lisa LaFlamme speaking publicly started the conversation. Contributions by others who have experienced similar treatment add human interest and weight to the story. But real systemic change happens when those not experiencing the prejudice also take up the challenge to call it out.

Ageism is a prejudice against our future selves

As our friend Ashton Applewhite says, ageism is a prejudice against our future selves. Every single one of us is ageing. What if those of us who haven’t crossed the threshold into “older age” fought today so our future selves don’t experience ageism tomorrow?

It’s not up to older workers to solve the challenge of ageism in the workplace. It’s up to leaders, managers, and employees of all ages to get better at identifying everyday comments, policies, and cultures that sustain ageist viewpoints and unequal relations of power. I talk about some simple, practical examples of these in this CBC interview.

Our leaders in the fight against ageism don’t have to be old. The goal shouldn’t be to profile as many stories as possible. The goal should be to learn from the stories, understand the nature of the issue, and champion change. Here, Challenge Factory’s 10+ years of focus on age and workplaces is valuable. We know that personal stories are powerful but not enough on their own for leaders to take the risk and construct new, updated approaches to talent management, training and development, succession planning, and intergenerational workforce development. Our organizations today are based on obsolete workforce and career models.

Our leaders in the fight against ageism don’t have to be old. The goal shouldn’t be to profile as many stories as possible. The goal should be to learn from the stories, understand the nature of the issue, and champion change. Here, Challenge Factory’s 10+ years of focus on age and workplaces is valuable. We know that personal stories are powerful but not enough on their own for leaders to take the risk and construct new, updated approaches to talent management, training and development, succession planning, and intergenerational workforce development. Our organizations today are based on obsolete workforce and career models.

I lay out the steps for CEOs, HR leaders, and frontline managers to dismantle and replace outdated organizational design in The Talent Revolution: Longevity and the Future of Work. These changes require a bit of trust and a lot of courage by both the people experiencing ageism and the managers who don’t want to be ageist, but are working within the systems they’ve inherited.

This isn’t just about the decision to let your hair go grey.

It’s about shaping a Future of Work in which everyone is valued, no matter their age. In the end, the real opportunity of this moment will have been realized when the airwaves are flooded with new, better stories—because we’ve left behind outdated career biases.